Photography by Jason Kaplan

How do you craft an icon, one that stays relevant for decades to come? A simple lesson from Portland-based Pendleton Woolen Mills: Don’t let history become history.

Consider how it all started: By the turn of the last century, some

3 million sheep called Oregon home, grazing its verdant valleys and windswept hills. After shearing, the wool would get scoured and untangled, ready to be spun into thousands of miles of yarn. The virgin wool didn’t need to travel far, with a sizeable share of those fibers making the short distance to a mill opened by the Bishop family in the frontier town of Pendleton, the origin of these unmistakable blankets.

Defining symbols of the American West, the first mass-produced Pendleton blankets were adorned with vividly stylized patterns designed by one Englishman, Joseph Rawnsley. After joining the company in 1901, Rawnsley spent months with Native Americans, replicating their ceremonial designs and merging those geometric motifs with European and Asian elements. The company’s tribal relationship soon grew reciprocal, with the blankets widely traded on reservations.

The rise of the Arts and Crafts movement in the early 20th century saw Pendleton blankets pop up in homes across the country, cementing their reputation as timeless interior design accents.

Today Pendleton operates some of the last-remaining woolen textile mills in the United States. Let’s peek inside to see how they click and whir, turning out thick and durable blankets much as they did more than a century ago.

Visit yourself to witness how Pendleton crafts each blanket. The company’s two mills — in Washougal, Washington and Pendleton, Oregon — offer free tours, Monday through Friday.

DYEING

It all starts with fleece, and much of Pendleton’s wool still comes from the Pacific Northwest, Oregon in particular. After grading, sorting and cleaning, the wool gets dyed — either as fiber, yarn or fabric, depending on how it will be used in the final product. Modern times have changed this process for the better: Computerized scanners evaluate fibers, generating and allocating appropriate dye formulas to ensure rich and consistent coloration.

CARDING

From fluffy to flatness: The term “carding” derives from the Latin word “cardus,” which translates to “thistle” or “teasel” — the natural tools once used to prepare raw wool for spinning. Today the brightened fibers go through a mechanical process that results in a fine sheet. That fine sheet gets divided into thin, continuous strips called roving.

SPINNING

Now things start to look familiar. After carding, the processed strands of roving get twisted into yarn and spun around a cylinder known as a bobbin. Steaming the yarn eliminates kinking, sets it and prepares it for weaving, the penultimate step.

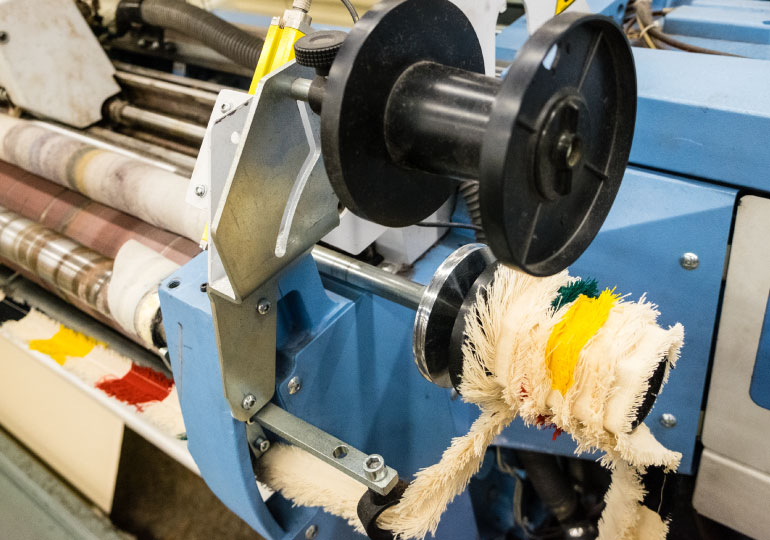

WEAVING

A blanket truly takes shape in the weaving process: A piece of machinery called a loom weaves two sets of yarn: the “warp” and the “weft,” interlacing them at right angles. The warp is lengthwise yarn wound onto a warp beam and loaded on to the loom. The warp then passes over and under the crosswise threads, known as the weft.

FINISHING

The blankets go through a few final finishing processes to control for shrinkage and keep them crisp and smooth. After inspection, they receive the appropriate edging or trim. The affixed tag reads “Warranted to be a Pendleton,” which guarantees each blanket lives up to the company’s legendary standards. And there you have it — how an icon stays an icon.