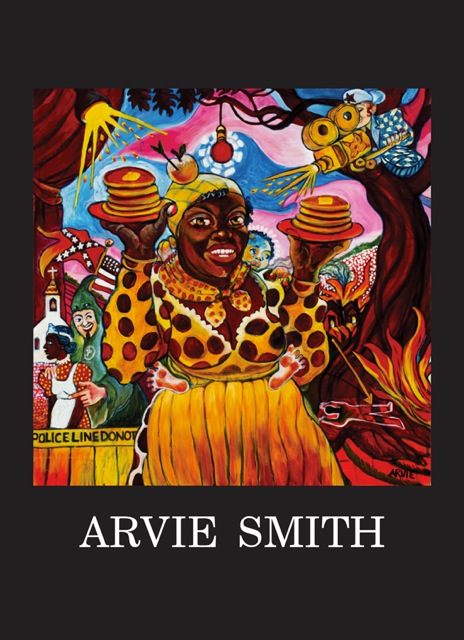

| “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!” |

“I love the idea that if “together we paint” could somehow be at least a great start to breaking through the decades and generations of mistrust and atrocity. I know Arvie does too. But, as we both know and sensitive and intelligent Americans know, we are right at this moment living in a time where we are once again facing an uncomfortable truth: that burying a sadistic past, a dance with horror and mayhem, is not that easy.” – Mark Woolley

Toast Arvie this Saturday, May 16, 5-9 pm at Mark Woolley Gallery (Top floor, Pioneer Place).

Save the date of Saturday, June 20 for an Artist Talk by Arvie, 1:00 pm, with another 5-9 pm reception as part of Third Saturday.

About Arvie Smith:

Arvie Smith is a Northwest treasure — for his work as a painter, storyteller and advocate who explores racial stereotypes in vivid works and compelling collaborative projects with incarcerated youth. He also has a long, distinguished career as a Professor of Art at the Pacific NW College of Art.

Having traveled to Africa at least 7 times, his masterful work has a cultural and historical richness that is rare.

In 1984, Smith received his BFA from the Pacific Northwest College of Art (PNCA) in Portland, after also studying at Il Bisonte in Florence, Italy in 1983. In 1992 he received his MFA from the Hoffberger School of Painting, Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, where he was teaching assistant to Grace Hartigan. It was while on the East Coast that, in addition to his genealogical roots informing his painting and drawing, he conducted intensive research to further refine his vision, including study at the Schoenberg Library of Harlem, the Library of Congress, Howard University and the Maryland Historical Society. On one occasion he visited an old plantation, sat on the steps of the slave quarters and he says, “felt the spirits move around me.” Smith is Professor Emeritus of Painting at PNCA, where he taught from the mid 80s until 2014. Prior to this, in addition to his time teaching at the Maryland Institute, College of Art, he was a visiting professor at the University of Oregon and Oregon College of Art and Crafts.

Curator’s Statement (Mark Woolley)

“Together we paint….”

Three words, “together we paint…” jumped off the page to me as I was reading a brief artist statement for a foundation award application by ARVIE SMITH, a beloved and important NW painter, who was describing his experience of working with incarcerated juveniles on mural projects, projects designed to give voice and meaning to their concerns about hope for their futures. After a collaborative process of defining and refining content, Smith creates the dominant image and then… “together we paint.” In Arvie’s own words, as an African American painter and professor:

“I transform the history of African Americans into two-dimensional paintings that depict deep sympathy for the dispossessed and marginalized in a search for beauty, meaning and equality. My work reflects injustice, the will to resist. It reflects the journey from bondage to freedom to opportunity to contributions of the African American in society, our country, our state. My grandparents raised me in Texas. He was a college history prof in an all black college. She was head teacher and principal for a separate-but-equal grade school. The KKK burned down my ‘uppity’ grand uncle’s farm. Great grandmother was a slave in North Carolina. Great grandfather stowed away on a ship from Jamaica and made a home in Texas. At 13, I was sent to South Central LA, where my mother worked three jobs to create a home for my siblings and me. I had never been in a world where children disrespected their elders. As a gang member, I was able to protect myself and my siblings. Gang membership offers black males a sense of fraternity and a sense of being in the absence of a father figure—then and now. My post-Obama work captures the celebration, the amazement, the hope, although the idea that blacks are seen as inferior continues. Obama’s election invites Americans to say: ‘I can be president. I see and feel the audacity of hope; the encouragement that yes, I am in no way inferior nor am I a second class citizen. I am somebody.’ Blacks depend on the largest of the dominant culture for recognition. In life, we filter everything, before we speak we must consider the consequences of our words. No black person feels secure in their position. Through art there is freedom. I expose the slights, discrimination, condescension. I speak unfettered of my perceptions of the black experience. By critiquing atrocities and oppression, by creating images that foment dialogue, I hope my work makes the repeat of those atrocities and injustices less likely.”

I love these words. I love the idea that if “together we paint” could somehow be at least a great start to breaking through the decades and generations of mistrust and atrocity. I know Arvie does too. But, as we both know and sensitive and intelligent Americans know, we are right at this moment living in a time where we are once again facing an uncomfortable truth: that burying a sadistic past, a dance with horror and mayhem, is not that easy. Hence Arvie’s current show at my gallery, which could not be more

important, timely, and powerful: “Tight Rope”, a collection of vivid, powerful works linking our troubled past to our equally troubled present is not an answer. It is a question: “How can we move ahead in a meaningful way when it comes to race, one of the most powerful divides?” As I just read today in TIME magazine, in an article by Tavis Smiley, seeking to make sense of the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore (a city that is part of Arvie’s past), his neck broken, and the ensuing civic convulsions:

“Democracy is threatened by racism and poverty. On April 4, 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. gave the most controversial speech of his life, ‘Beyond Vietnam.’ A year later, to the day, almost to the hour, he was assassinated. In that speech he had pointed out a triple threat facing America: racism, poverty, and militarism. In 2015, what are the issues still threatening our democracy? Racism. Poverty. Militarism. Are these riots or is it an uprising? Semantics. Detroit then (1968) was a chocolate city. Baltimore today has a black mayor, a black police chief and a black President of the United States. And they are powerless to stop it. These riots aren’t a black or white thing—they’re a humanity thing. When the mayor and the police chief and the President cannot explain why Freddie Gray is dead, somebody’s got to be held accountable. Today, you don’t have the Klan, and you don’t have Emmett Tills or Medgar Everses, but it’s more insidious in that preditory policing is happening under the rule of law. Sadly, when these incidents happen, we have a sort of fake and fleeting national conversation about police misconduct and race relations. And then we return to business as usual. Until it happens again.”

I believe it is important to note, that, although I agree with the sentiments of Tavis Smiley above, it is actually premature to say that “we don’t have the Klan,” unfortunately. The Klan still exists and a simple Wiki search reveals that sad fact. The Klan has dispersed into smaller factions and is present in “cells” all over the world, albeit with name variations, such as “The 6th Era of the Klan.” Human society has not seen the last of the Klan and we must remain vigilant when it raises its ugly head, just as we have to remain vigilant about rogue terrorists, some “homegrown”, who selectively use twisted Islamic ideals to justify killing and mayhem.

So, as we continue hashtagging the unarmed victims with sickening regularity: Eric Gardner (#I can’t breathe), Michael Brown, Travon Martin, Walter Lamar Scott and so many others, there has to be a way forward. Arvie Smith lived in Jasper, Texas with his grandparents and just in that small town, James Byrd in 1992 was dragged by a chain behind a pick-up truck and Alfred White, a young black man, was killed in police action in 2014. One way forward for blacks and whites who still hope and dream for a different reality is ART. It lasts. And it changes lives and preserves memories. In the case of ARVIE SMITH, this art is masterfully done, simultaneously formidable and humorous, connects our checkered past with a delicate present, and makes one smile and also grimace while thinking of a different reality that always seems just beyond our grasp. That is why I am so very proud to host this show. Tell everyone you know. We are on a “Tight Rope” and we can’t afford to fall off. Every time there is a police killing of an unarmed black man that goes unpunished, racism is rewarded. I would also like to note that last year 126 officers in the U.S. died while trying to protect us from ourselves. They also deserve to be remembered and honored. We are all a part of a big, dysfunctional family, but I know that through the thoughtful expressions of artists like ARVIE SMITH, we will hopefully understand our illness just a little bit more. And maybe go out and talk to someone. Or maybe hug them. Yeah, that’s the ticket. It’s a humanity thing.