The expansive covered porch at the front of the cabin features a built-in grill and a 6 foot long table. The perfect spot to relax with friends and family while enjoying a meal ‘al fresco’.

Photos by Bruce Forster

The word “cabin” is typically defined as a small house of simple construction conjuring up images of a rustic log structure deep in the snow or an isolated lakeside fishing cottage. Bruce Forster and Gin Flynn’s vacation home carries on in the tradition of the simple retreat, nestled in a forest dotted with silver aspen and heritage oaks, but this cabin is unique in its form.

Barely 60 miles east of Portland, the town of Hood River is a bustling outdoor mecca above the banks of the Columbia River Gorge. The town known as the Windsurfing Capital of the World, has equal appeal to those looking for amazing food, wine and natural beauty. This lush landscape, carved into the Cascade Mountain Range, had long been a place for Bruce and Gin to spend time with lifelong family friends. Spending long days skiing at Mount Hood, the friends would often stop for the night in Hood River. Enjoying a last night of serenity from the bustle of the city, where the couple worked as an artist (Gin) and a photographer (Bruce). Their lifelong dream of being able to own a slice of Hood River paradise came to fruition in 2003, when land that had long been used as cattle pasture, was subdivided and sold.

Spring-green cabinets and a wall of mosaic glass tiles brighten up the cabin’s kitchen; the Danish wood-burning stove is not only beautiful, it is environmentally friendly.

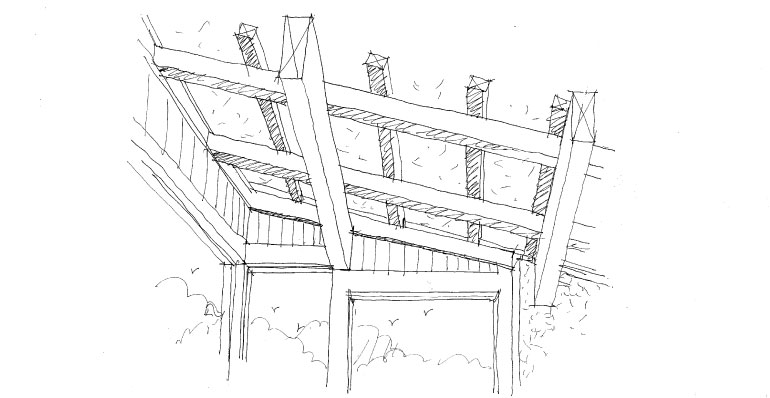

a view of the exposed articulated framing structure at the eaves of Forster’s studio

The 5 acres where the Forster/Flynn cabin sits is a serene site bordered by a strand of silver aspens toward the east, a seasonal creek at the south end and lengths of old rock walls. The stacks of basalt rock are well-worn vestiges of the region’s volcanic activity; one massive rock, easily 10 feet in diameter, sits centered on the site, providing the perfect spot to lay back and take in the sky. “We call this home rock,” explains Bruce. “In the summer it soaks up the sun, and you can lie on it at night and see the incredible night sky with the warmth still at your back.” Also notable on the site are several groves of ancient oak trees, providing a welcome canopy of shade in an area known for its hot, dry summers. Native grasses, colorful wildflowers and wild rose hip bushes fill in the remainder of the land, providing a continuous, changing palette as the seasons shift.

The convection stove is designed to burn at a high efficiency and limit smoke-particle emissions.

Soon after acquiring the land, a long summer weekend was devoted to building a simple wood platform within one of the oak groves. As time permitted, the couple would take time out of their busy schedules to camp on the platform along with their golden retriever, Tommy, shedding that urban regularity to take advantage of a slower pace and allowing themselves to learn a bit more about their surroundings each time they visited. They discovered views that inspired their art, an inky black sky crowded with unimaginably bright stars, birds whose migrations became familiar and high winds that thrill windsurfers but sent Tommy into hiding. And they dreamed about building a simple retreat that celebrated all of this.

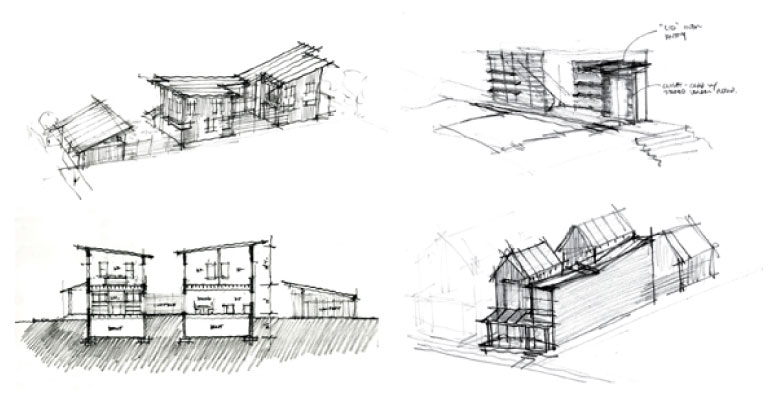

Designing a home that sat lightly on the land with a simple modernist approach was the challenge undertaken by Richard Brown, of Portland-based firm Richard Brown Architect. Brown had worked with Forster previously, designing a studio for his professional photography business, and forged a friendship with the couple. Having spent time with Forster and Flynn on the wood platform within the oak groves, Brown was intimately aware of the site’s attributes and how best to retain the integral spirit of the land. Initial schemes of the house show a much larger structure, articulating its spaces around the oak grove like a boomerang, as satellite studios for each artist sat independently from the main house. As design progressed, the plan became more simplified and rectilinear. The resulting cabin is found at the end of a long curved driveway passing by the one lone outbuilding, which houses Forster’s studio and is affectionately referred to as “the bunkhouse.” The dark charcoal stucco on the exterior, coupled with the warm cedar siding and ribbed steel roof, were materials chosen to age gracefully over time and visually relate to the mineral palette of the rural site. Utilizing enduring elements was a priority for Brown, ensuring that this cabin was easy to maintain and capable to be passed on to future generations.

Bruce’s studio, affectionately nicknamed the “bunkhouse”, sits a few yards from the main cabin amidst the native pasture grasses; (sketches) architect Richard Brown’s sketches describes the layered Douglas Fir ceiling at the window (at top) and the contrast between the thick RASTRA block walls and the roof framing (at bottom).

A door off the study leads to a private patio on the South side of the cabin. Deep overhangs shield the tall windows from the summer sun

At first glance, the cabin’s angled shed roofs belie its modest 1,800 square feet. A covered flagstone terrace, equipped with a large built-in grill and a six-foot Douglas fir table, extends the living space to the exterior beneath a generous wood soffit. “The intent with this cabin was to have a place for friends and family to gather and share good stories, good food and good drinks inside or out,” explains Forster. The front door opens into a soaring space above a smooth, radiantly heated concrete floor, sharing the functions of the kitchen and the dining and living rooms. Thoughtfully placed niches on one side house the couple’s ample collection of books and art, and on the other a Danish wood stove. The room ends with a wall of windows 12 feet tall, framing the view of that celebrated oak grove. A few feet beyond this, no less than 10 birdhouses stand in the grasses welcoming the familiar swallows. “We asked for a space that had plenty of natural light, a comfortable space that took advantage of the pastoral views,” the couple explains.

Architect Richard Brown’s sketches describes the layered Douglas Fir ceiling at the window

Off the main room, by way of a rolling barn door, lies Flynn’s study. A quiet room with beautiful southern light, the space allows the flexibility needed for creative pursuits. The cozy sleeper sofa easily extends to accommodate overnight guests, and rolling tables stow out of reach, which has proved handy with their daughter and new infant granddaughter, Arabella, paying them frequent visits. Down a small hallway sits the bedroom, which fronts a private courtyard resonant with the soothing sounds of a small water fountain. The remaining room is the bathroom, outfitted with smooth pebble floor tiles and a wall of glass made of salvaged bus windows. Every room in the home is independently connected to the exterior by way of Dutch doors, and the bathroom is no exception. A milky glass door leads to an outdoor shower, where you can shower au naturel while enjoying the scenery.

The use of salvaged materials is not limited to the bathroom’s wall of glass: TriMet bus windows artfully shattered and tinted with green acrylic. The kitchen’s countertops are crafted from wood salvaged from bleachers removed from a high school in the neighboring town of Mosier. Therepurposed seats provided Douglas fir counters from trees hundreds of years old, with beautiful clear wood free of young wood’s imperfections. The crisp modern interior provides a calm background to the couple’s artful assortment of antique and modern pieces, each with its own story to tell.

The open design of the main room visually connects to the stud. Pocket doors at both rooms provide privacy when needed; glass panels, salvaged from TriMet bus windows, glow in the sunlight.

The whole of the interior is sheltered under what appears to be an intricately crafted wood screen. The crisscross of fir timbers sit in stark contrast to the black ceiling above, punctuated only by square skylights above the kitchen. The latticework is reminiscent of finely crafted Japanese screens, which brings visual texture to a space typically left bare. Expertly crafted by Hood River contractor Scott Sorensen, the resulting sculptured ceiling creates a dynamic vaulted space, much larger than one anticipates; similar to looking up into a canopy of trees toward the sky beyond.

Traditional cabins, made of logs, benefitted from the thick walls that would help mediate the indoor and outdoor temperatures. To emulate this passive strategy for heating and cooling, the walls were constructed with Rastra blocks. This is an innovative type of construction where insulated concrete forms (modular units) are dry-stacked and filled with concrete. This high-performing system allows the formwork, made from recycled foam plastics, to stay in place, creating a very energy-efficient structure. The resulting walls are approximately a foot in width. The mass of the walls maintains interior heat well in the winter and, in the summer, helps keep the heat outside and the interiors cool.

The couple lists the things they love about their retreat: the warmth of the wood against the white textured plaster, the craftsmanship of the exposed structure, the attention to detail, the wall of windows framing the views and the way that light plays within the space, changing with the seasons. “All I wanted was to wake up and see trees, see space,” recalls Flynn. “In my Portland home I wake up to a view of my neighbor’s carport.” Having this place away from the everyday world has provided a new perspective, a quiet place allowing introspection and peace. Forster is working on an ongoing photo collection investigating the drama of the area’s cloud formations and also appreciating the opportunity to revisit projects and images, which he shares from his personal work archive housed in the studio. Flynn describes her time at the Hood River house as “dream time,” illustrated as being present and engaged in the country distractions, such as the backlit grasses, the migrating birds and the seasonal changes in the landscape. “We love how un-fussy this place is; there’s a wildness about this site that the cabin supports with its simple form,” Gin says. “We come here to regenerate and relax. We read, nap, cook and sometimes …. nap again.”

The master bedroom’s neutral palette is set off by a colorful wool rug, inspired by the landscape just outside the window. The concrete floors are radiantly heated, providing even warmth throughout the home.

A cherished photo album sits on the coffee table, documenting images of not only the land but of everything sharing this acreage: flora and fauna alike. Scattered within are photos of the cabin slowly taking shape through three years of construction. The final image shows a cabin that blends into its beautiful, rugged setting, quietly harmonizing with the autumn leaves surrounding it. Artfully transcribed on the first page is a short poem christening the spirit of this home:

Hood River House

This house shelters day dreaming,

this house protects the dreamer,

this house allows one to dream in peace.

A path of crushed gravel leads to the cabin’s welcoming entry, sheltered under a generous wood soffit