Andy’s lifelong love for found objects and art helped him zero in on the more interesting elements in the original cottage, which he used again within the new residence.

Written by Elisabeth Dunham | Photos by Leah Neah | Styling by Nicole Callaghan and Emily Jean Craker

As a contractor who specializes in historic preservation, Andrew Curtis is naturally drawn to homes that come with a good story. So when he first saw the Irvington Heights cottage that he would eventually transform into his home and office, he was more interested in what he was hearing than what he was seeing.

“The house was humble, architecturally,” recalls Curtis, owner of Full CircaInc. Vintage Remodelers in Portland. “But an older couple had lived there and one of them had passed away. Their daughter told us her grandfather had lived in the yard for two years in the early 1920s while he built the house. He carried lumber — V-groove shiplap siding, tongue-and-groove wainscoting and framing — from the Irvington area, where they were deconstructing 1870s farmhouses.”

Frames made with salvaged materials

|

Hearing the story led Curtis to examine the structure more closely, and sure enough, the width of the lumber — slightly thicker than would have been used in the ‘20s but consistent with early Victorian dimensions — substantiated what the homeowner was telling him. In other words, Curtis was about to salvage and restore parts of an old house that had been built from even older salvaged materials.

Andy sitting on the stairs — the

|

Curtis, a contractor with degrees in art and historic preservation, initially envisioned a painstaking historic remodel that would enlarge and modernize the cottage while preserving the recycled elements and other charming features. After all, that’s what he did for a living. However, in his decades-long contracting career that included numerous renovations and restorations of historic homes throughout Oregon and Washington, he’d never constructed a new home from the ground up.

“I see my job as reading the building’s story,” Curtis says. “You have to be able to not blindly rip into something, but instead realize the treasures that are there, and the intent of the original builder. And if you respect that, you wind up with something really special.”

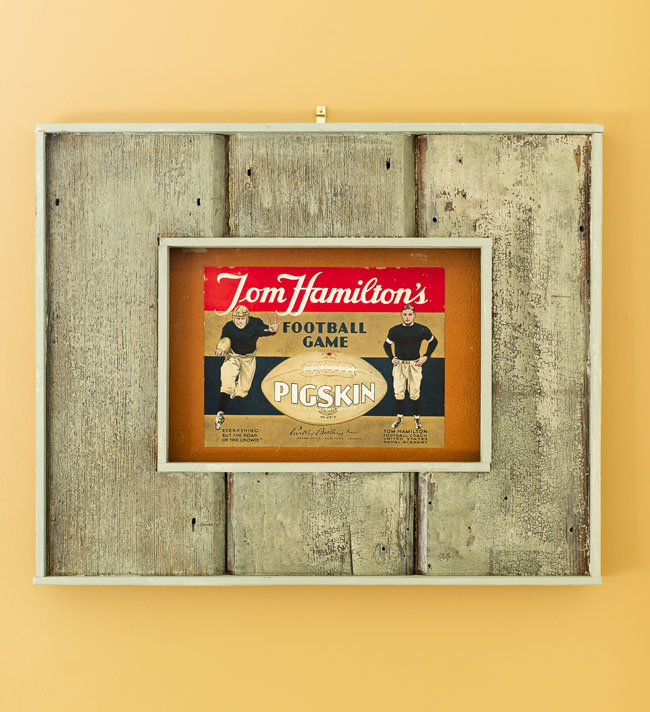

An 80-year-old football charting game

|

But as is often the case with older residences, when Curtis and his architect took a closer look, they soon realized that updating the cottage was not going to work. Interior spaces were small, dark and cramped. Windows were uneven and there was no insulation — unless you count the boards that were nailed to the outside and inside walls. The biggest problem was the foundation, which had not been poured with the right mix of ingredients to withstand an expansion.

“That was the hardest thing: to say that this little house doesn’t grow up, but just gets dismantled. And that’s the best we can do with it,” says Portland architect Sue Collard, Curtis’ longtime collaborator. “Andy and I are both old house people and that’s the way we come into a project. We went through many rounds of talk- ing about it. I stood in the attic, I measured and drew plans. But there wasn’t anything we could save to make it work.”

“So we wound up using the materials and honoring them in a different way.”

The footrest was cleverly made from an old handrail

|

Today, the 625-square-foot Workers Cottage is gone, replaced by a generous three-story Craftsman Colonial-style residence that Curtis and his crew built from the ground up, after going to great pains to dismantle and restore every usable board and make them work in the new one.

The crew lifted the entire floor structure into the neighbor’s yard on cribs while they excavated the basement and built a new foundation then placed the floor structure back onto the new foundation. As they carefully dismantled the cottage they saved the Victorian wainscoting and V-groove shiplap siding so they could restore and repaint it for use in the new home. At the same time they salvaged pieces from other historic homes they were working on simultaneously and later, they were able to include them in the new construction.

The 1800s wainscoting became a focal point in the new kitchen area, where it was used to sheathe the ceiling. It blends smoothly with other rich wood detail on the main floor, everything from casework and molding to cabinets and custom furniture, all created from a mix of salvaged and new materials. Similarly, the antique V-groove shiplap siding originally from an old Irvington farmhouse got a third life lining an accent wall of the hallway between the main entry and the kitchen. Elsewhere, Curtis and his carpenters used the same siding to create furniture and picture frames.

Window seating and a braided rug

|

And just as the earlier home’s personality comes through in the new house, Curtis’ personality comes through not only in the collage-like interior design but in the artwork and furnishings that reflect his unusual personal history as a college football player — and later coach — and architectural history and art lover.

The attention to detail is what makes him at the top of his game when it comes to building and restoration. “This is not just another Craftsman-inspired house like others popping up throughout Northeast Portland lately, but a residence solidly constructed by a team of master craftspeople,” Collard says.

“The thing I love about working with Andy is I can give him a pretty basic set of drawings and I know that every detail is going to have attention lavished onto it,” Collard says. “He knows how old houses were put together and he’s got all these ways to transform that into the present day.”

Curtis sketched exterior views and a rough first-floor plan before handing them over to Collard, who refined the design, completing the engineering and the permit drawings. He credits his lead carpenter Isaac Schmalz with helping him to execute his mix of salvaged and new materials in a way that is seamless and updated rather than hodgepodge. “I’m lucky to have a team made up of talented artisans and craftspeople that I can call on as needed for this type of collaboration. We’ve been in the business of remodeling for 24 years and preservation always guides the process,” Curtis says.

Turning salvaged materials into high-end construction “is probably more work than I would wish upon anyone,” he adds, “but I love the artistic process, collaborating and never quitting until you end up with something that is well conceived and beautiful.”

Movable bike storage piece,

|

He bought the house in 2005. After several years of planning and consideration he handed over basic floor plans and sketches to Sue Collard. Construction took place on weekends and after work over the course of another three years.

Dining room hutch designed

|

And while most people wouldn’t see building a three-story house where a tiny cottage used to be as a simple project, Curtis says that simplicity is at the heart of what he does.

“I have a sensitivity to the nice stuff and to what is worth saving and what is not,” Curtis says. “As a preservationist you try and simplify. This house was a chance to use what I’ve learned from so many wonderful old homes, to borrow those lessons and create the spaces I wanted for my own home. The third time around for these salvaged materials, was a charm.”